This Genius Idea Might Be the Key to Transforming Your NYC Commute

From the time he first stepped on board an airplane as a 7-year-old, Craig Avedisian ’84 fell in love—first with flying—then with all the other things that keep people and things moving. You could say this Florida Tech grad has an affinity for all things transportation.

“We took a family vacation to Wisconsin and flew there,” Avedisian said. “It kind of blew my mind. I really couldn’t wrap my head around it at 7 years old, but I thought it was the coolest thing that we’d gone so far so fast. So I was hooked with the aviation bug early.”

“We took a family vacation to Wisconsin and flew there,” Avedisian said. “It kind of blew my mind. I really couldn’t wrap my head around it at 7 years old, but I thought it was the coolest thing that we’d gone so far so fast. So I was hooked with the aviation bug early.”

He went on to earn his private pilot’s certificate at 17, by 19 had a commercial certificate with instrument and multiengine ratings and Certified Flight Instructor certificate, and graduated from Florida Tech in just three years with a degree in air commerce/flight technology. Although he never worked as a commercial pilot—too much autopilot for his tastes—he did remain in the transportation field. After graduation, Avedisian spent 13 weeks bicycling through Europe, before starting a managerial job at a courier business in California. He then went on to become a dock supervisor for a national trucking company and eventually worked with consultants involved in San Francisco’s city planning. When he decided to go to law school, Avedisian began to work with judges at the National Transportation Safety Board who decided enforcement actions brought by the FAA against pilots.

Now, an attorney in Manhattan, he primarily deals with real estate and commercial cases. However, he uses one of the largest mass transit systems in the world on a daily basis—an aging subway system that struggles to keep up with ever-increasing demand in a booming population. New York’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) needed innovative solutions for some large problems on a tight budget, so New York Governor Andrew Cuomo announced the MTA Genius Transit Challenge, a global competition.

With Avedisian’s background in transportation, and his knowledge of the New York City system, it’s no surprise he jumped at the chance to put in his two cents. What is surprising is that he won.

High Capacity

The MTA received 438 submissions from 23 countries, most of which were supplied by large transportation industry conglomerates, not individuals. The task was daunting. There were three phases to the competition, each one narrowing down entries and requiring more submissions.

“Once I made it past Phase One, I had a fair amount of confidence in the idea,” Avedisian said. “If I can prove this works, it can win. All I really didn’t know was what I didn’t know, which can actually be an asset, as people in the industry can often be ‘too close’ to a problem.”

Avedisian’s idea helps increase capacity, without spending a lot of extra money or upgrading with expensive technology. All you have to do is add cars, while stopping those cars at the front and rear of the train at alternating platforms. For example: On a 14-car train, the first four cars and the last four cars take turns stopping at alternating platforms, while the center six cars stop at every platform. Essentially, overshooting and undershooting every stop. Passengers know which cars to board by standing at color-coded areas of the platform. The center cars serve all stations for anyone who prefers or needs that service.

“As I thought more about the idea itself, I realized how huge the increase in capacity was,” Avedisian said. “I figured out there was a compounding effect of using more modern rail cars that increased the capacity as high as 65 percent, instead of just 40–50 percent.”

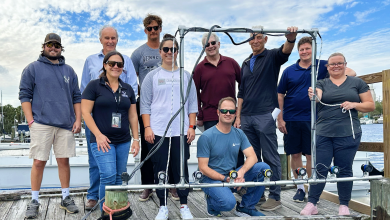

It all seems so simple, but the process to arrive at such a streamlined result took months of research, phone calls to England and Finland to learn more about their systems and technology, multiple drafts of a 30-page proposal and an interview before the panel of judges for the challenge.

“When I went into that interview, my first goal was not to embarrass myself,” Avedisian said. “As an outsider, I thought ‘I just want to perform at a [reasonable] level. If I give an average performance for somebody who’s in the industry, I’m going to be happy.’ Of course, I wanted to do better than that, and aimed to do better, but that was the minimum I wanted to achieve. I prepared for three days for that interview.

“I’ll quote Bruce Springsteen: ‘You need confidence, but you need fear too.’ It sounds bizarre, but it’s true. You had to have confidence to enter this contest, but fear is a real driver. It’s an engine. You can’t let it overwhelm you or you lose the confidence, but some amount of fear is healthy. I did not want to screw this up.”

Certified Genius

Avedisian had just the right amount of fear and preparation. He was announced as a winner on March 9, eight months since the start of the challenge.

“I’m not running around like a lottery winner even today,” Avedisian said. “I think the idea is incredibly powerful. The idea is roughly 12–13 times more cost-effective than building new subway lines to expand capacity. There’s just nothing that competes with that.”

More than anything else, Avedisian credits his success with the transportation knowledge and experience he has gained over the last 30 years, beginning with Florida Tech.

“My first sense of how to be a professional came at Florida Tech with the pilot training, because it is life and death up there,” Avedisian said. “Aviation concepts are not all that different. Transportation concepts are transportation concepts. I think every job I ever had mattered. I know I had subjective thoughts about virtually every one of them. The law is about persuasion. Scheduling is a big deal with aviation, and it’s an even bigger deal with trains. It all mattered.”

Although a copy of the $330,000 award check will be framed and hung proudly on his wall, this was never about the money. It was about what the check represents.

“If the day comes when I step onto a platform and my idea is implemented, and these giant, 85,000-pound subway cars are doing something different because of my idea, I think that will be the single-most satisfying moment,” Avedisian said.

Next Stop

This is not the last stop on Avedisian’s journey that began on that family vacation to Wisconsin. He will continue to follow an often unknown route from “Point A” to “Point B,” allowing his curiosity and love for transportation to take him to his next destination.

“What I’m most excited about is that I have some other ideas,” Avedisian said. “I might start doing a little transportation consulting too. That is where my heart is.”

Craig Avedisian’s Award-Winning, Capacity-Expanding MTA Genius Transit Challenge Idea

Say an average subway platform can accommodate a 10-car train. Avedisian’s concept allows for the addition of more cars without changing current infrastructure. The extra cars simply don’t offer passenger access at every platform.

For example, on a 14-car train, the first four cars and the last four cars take turns stopping at alternating platforms, while the center six cars stop at every platform. Essentially, overshooting and undershooting the platform at every stop.

Passengers know which cars to board by standing at color-coded areas of the platform. The center cars serve all stations.